Recently I had the opportunity to participate in a documentary about ransomware. The journalist that conducted the interview (not with me unfortunately) wanted to see how malware in general works and how ransomware acts.

The WannaCry ransomware

First, let us start with the definition of ransomware. A ransomware in general is a software that steals your data and asks for a ransom (most often money) to have it back. Now as you know, you can not really “steal” data, but you can duplicate it, delete it, or even worse: encrypt it. Most ransomware samples you hear of use some kind of encryption to corrupt a victim’s personal files. The goal is to lock up the most valuable documents of a person, such that the person is inclined to pay up to have their data back.

I had already set up a virtual machine to explore the WannaCry ransomware. WannaCry (or WannaCrypt) was a ransomware that caused a lot of news in 2017 as it targeted and infected a number of hospitals in Great Britain, as well as several known companies, such as the telecommunication company O2, the German train service Deutsche Bahn and over 50 other companies around the world. The virus made use of a vulnerability called “EternalBlue”, originally discovered by the National Security Agency in the US, then later leaked by a hacker group called “Shadow Brokers”. You can see why this ransomware hit the news.

More impressing than the actual infection was the “defeat” of an initial version of WannaCry by the security research Marcus Hutchins aka MalwareTech. In short, Mr. Hutchins found a “kill switch” inside the malware, and was able to prevent further infections by registering a domain. You can read the original story on his blog if you are interested in technical details or read the highly suggested story on WIRED about his arrest and the mind-blowing legal theater by the USA.

What does it feel like to be infected?

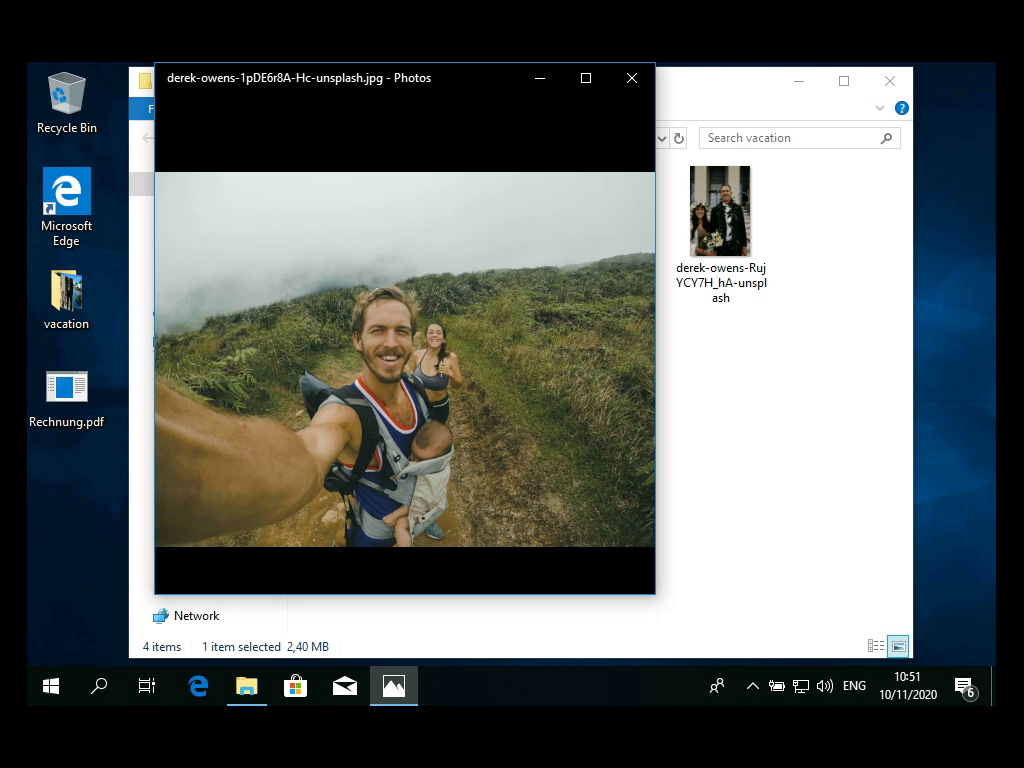

Only few people have experience with malware that attacks personal data. Most users simply can not imagine what it is like to have “a ransomware” on your computer. That’s why I built myself a machine to simulate it. For this, I had some “vacation” pictures from the Internet (courtesy of unsplash.com) and your generic Windows 10 installation.

In the screenshot you see a “vacation” folder with pictures, but also there is a PDF file called “Rechnung.pdf”, which is German for “bill”. So the scenario is that I received an email with a bill to pay.

What you (and the user) do not see: since Windows hides file extensions by default, the actual file name is “Rechnung.pdf.exe”, which is not a document but an executable software file. So this is the malware in question.

So, what happens if I open the “bill” file? See for yourself in this 2 min. video (fullscreen for full experience):

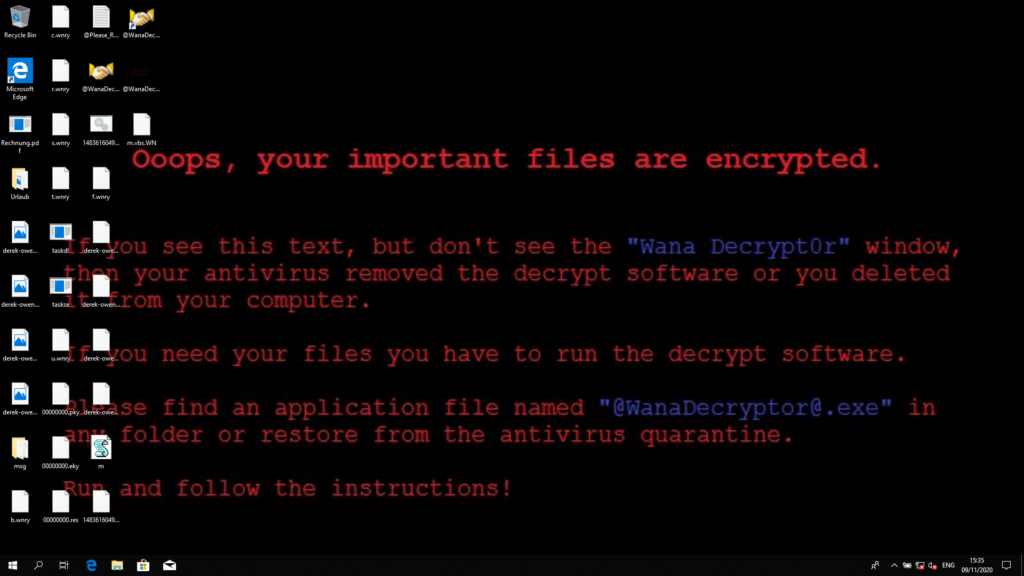

If you can not see the video, here is a description. Upon opening the file, some files appear on your desktop. None of them are viewable, and the file names are weird. The processor fan on your computer starts to spin up quickly. After a while, your desktop background changes to a black screen with a red message “Ooops, your important files are encrypted”.

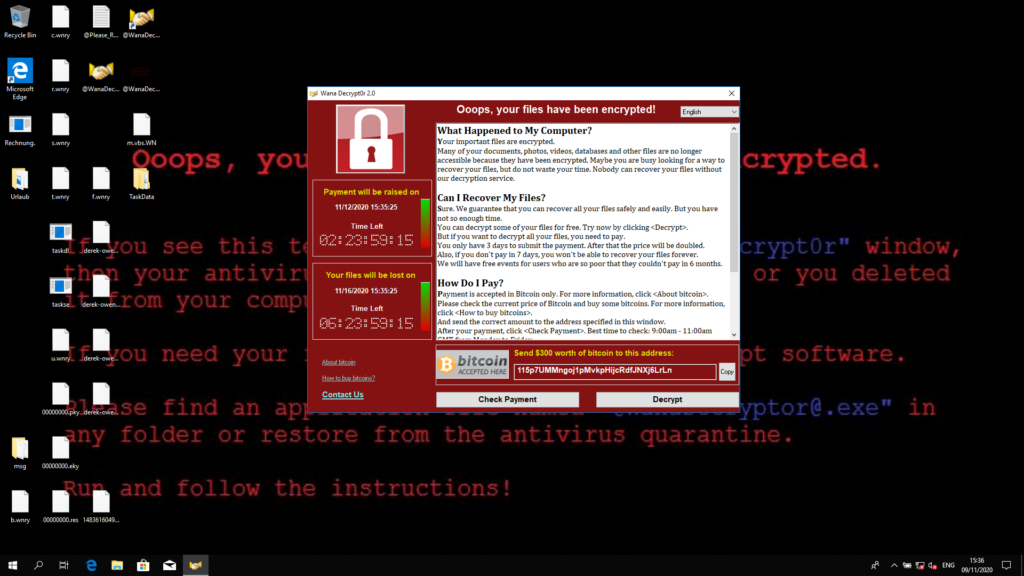

When this message pops up, your vacation files are already gone. You can still see some files in the folder, but none of them shows a thumbnail (the preview picture) anymore, and opening them does throw an error. Shortly after this, a window pops up that requires your attention:

The window shows threatening countdowns (to create pressure), a FAQ section on how to recover your files (spoiler: you need to pay) and instructions on how to buy and send Bitcoins, a digital currency that is difficult to trace back to actual persons.

The process is pretty fast, and the ransomware is really mean: it injects itself into other processes such that you can not kill it easily. Even though you close the window, it will open again after a while. A restart of the computer does not help, and your data is not recoverable.

But how do people get their data back?

This is probably the most urging question, and the answer is complicated and depends on a number of factors. The possibilities are:

- Pay and Pray

- You pay the ransom and hopefully the ransomware authors receive your money, get back to you and send you the key to free your private data. This does not always work reliably as criminals could just get the money and run. On the other side, the most successful (read: profitable) ransomware campaigns work by making the decryption as easy as possible for paying victims. People are more probable to pay up if they successfully recover their data afterwards, and the word spread fast when such things happen globally.

- Do not pay and pray (for a decryptor)

- Some ransomwares in the past were very simple. Either their encryption was very weak (and the secret key could be guessed) or the files were not encrypted, but simply renamed or hidden. When this happens, you can just hope that some knowledgeable person or company writes a “decryptor” software that frees up your private files. Since every ransomware is different, it is pure luck if your files can be decrypted that way.

- Do not pay, clean the infected computer and restore files from a backup

- This is the optimal solution. The big assumption is that you (or your company) have backups, these backups are not attached to the infected systems (or the backup might be also affected by the ransomware) and you can prevent another infection.

Unfortunately, ransomware can mutate, and this also happened with WannaCry. Once the kill switch was detected and made public, the authors changed their code and a new wave of infections. So not only had people problems getting rid of it, but they also needed to update all their Windows systems to stop futher spreading.

Malware research 101

At last I want to describe to you how I set up this experiment. I used a VirtualBox virtual machine, installed Windows on it and configured it. There are some things to consider:

You need to disable the network on the virtual machine. Whatever you execute in the machine should not escape and/or be connected to your host machine or to the Internet.

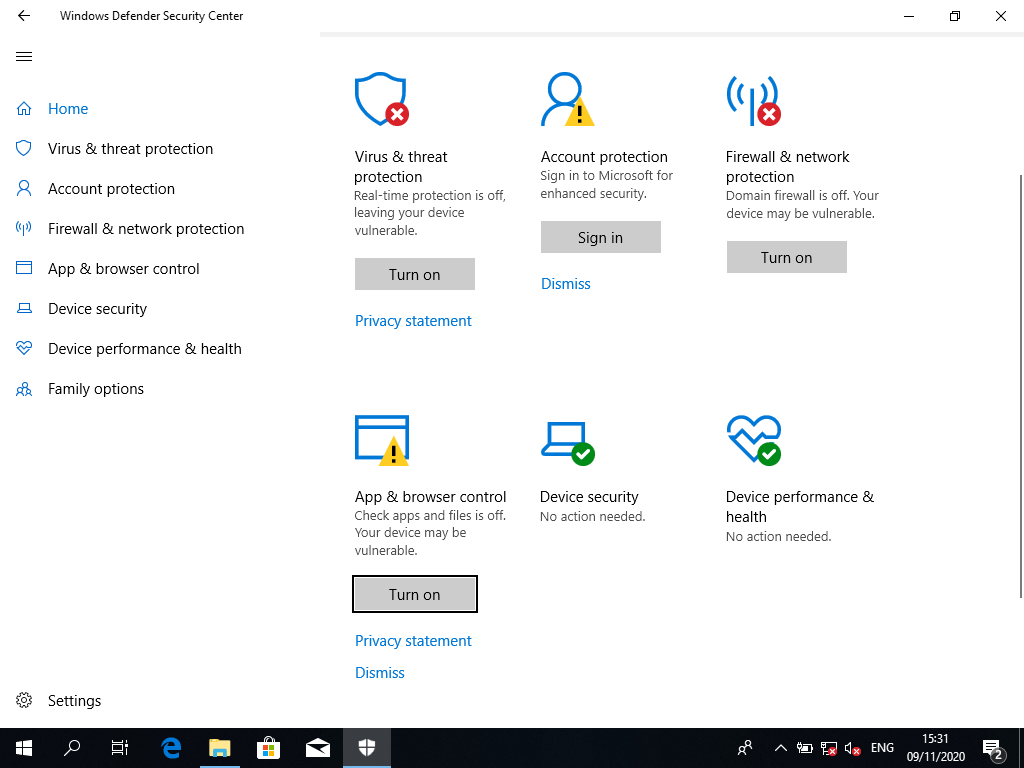

As WannaCry is known to most antivirus programs, any attempt to put it on your freshly installed Windows machine will fail:

I had to disable Windows Defender in several places:

The best thing to do then is to do a “snapshot” of the virtual machine. A snapshot is like a “savefile” that you can return to when things go wrong and you want to restore a safe state of the machine. It is also a great way to have a repeatable process.

Unfortunately I can not share the VM, as with the Windows OS installed in it I can probably get sued by Microsoft. You can download evaluation versions of Windows all over the internet, and there are even prepackaged VirtualBox images on Microsoft’s website that you can use.

Be First to Comment